Entertainment

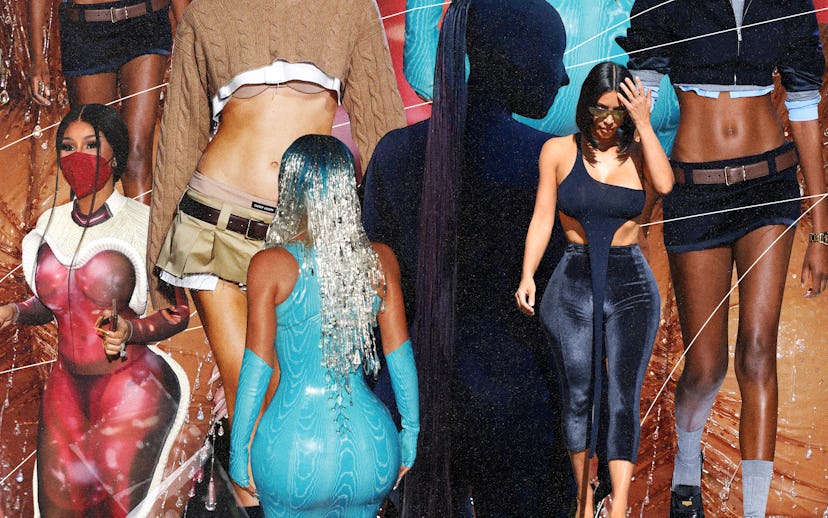

Miu Miu Mini Skirts, Kim Kardashian & The "End Of The BBL"

What a shift in fashion says about body politics.

Outside of the 2013 Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week in New York City, the crowd was in a frenzy. A sea of iPhone 5s rose as each front-row guest pulled up in their black car, with the crowd buzzing each time with the rumor that this must be Kim and Kanye. 2013 was the year that Kim Kardashian officially arrived in the world of fashion — this after years of talk that the reality star (her show then on Season 8) had been banned from the Met Gala, on the direct orders of Anna Wintour herself. 2013 was the year that had seen Kim’s engagement to Kanye. In 2013, the couple attended the Met Gala for the first time, a very pregnant Kim in an all-over print dress and matching gloves, styled by Riccardo Tisci, who, along with West, would see to Kim’s image being remade in the world of couture.

By 2013, Kim’s sense of personal style had made a mark on culture, mostly by the way of “body conscious” clothing: button-up blouse bodysuits paired with high-waisted trousers, skimpy tank bodysuits with “wet look,” high-waisted pleather pants. But most of all, there were the tight mini dresses by Herve Leger under Max Azria of BCBG fame, who acquired the fashion house in 1998 and began designing under the 2007 relaunched Herve Leger brand. Under his own direction, the designer moved beyond the brand’s classic ’90s “bandage dress” to a more embellished body-con a look that would be knocked off by Balmain and (before that) Bebe.

Despite her history with the brand, Kim was nowhere to be seen at the 2013 Herve Leger show, the year Nicki Minaj sat front row. I was seated in the back with Danielle Final, a fashion illustrator. As we waited for the show to begin, we discussed the insanity of the shows. “Fashion is like politics. It’s a war,” Final told me, as the lights darkened.

Fast-forward to the era of the pandemic: The past two years (or four in fashion years) saw a flood of videos and digital lookbooks in place of physical shows. The Miu Miu Spring 2022 show adhered to “the new normal” by livestreaming the catwalk. The physical and virtual spaces of the show were punctuated with videos by artist Mariem Bennani, in order to fit the short attention span of a digital audience. The looks were also suited to the tastes of a (younger) online audience, most notably the ultra-low-rise Y2K throwbacks (including a much tweeted-about low-rise khaki micro-mini skirt). The show toggled between early aughts silhouettes on the runway and ultra-filtered trippy alterations of the crowd, and ended with a short film in which a group of women laugh about a form of plastic surgery, commonly known as a “BBL.”

So why do they get their ass done? one woman asks. How am I to know, another woman answers. They take it from the thighs and inject it into the butt, says the third, and the women continue to laugh. The dialogue ends, the message virally interspersing with the clothes; then the video cuts back to the end of the show, models strutting in the super-low-rise outfits, hip-bones bared.

Fashion relies on transformation, even when it looks like regression. Y2K style has been a hashtag for years now, on platforms like Depop, Pinterest, and Instagram, with fast-fashion websites offering dupes of moodboard photos that veer into cosplay territory (the Cher Horowitz Clueless yellow suit comes to mind — although a ’90s callback — as well as the remake of the 13 Going on 30 mini dress). When nostalgic trends resurface on the runway, it typically isn’t as an exact replica of designs from the past, but more so the idea of the time period, with the cuts and silhouettes updated to contemporary sensibilities and notions of beauty. However, the visual shock of Miu Miu’s Y2K silhouette is that the micro low-rise mini skirts truly look as if they could have been pulled from the archives of Paris Hilton’s early aughts closet.

The current cultural climate, if not hinted at in the design of the Miu Miu skirt, is maybe more apparent in the short film, poking fun at BBLs. The past few months have seen a burst of discourse online about “The End of the BBL”; searching the phrase on Twitter brings up dozens of comments — users celebrating its imagined “demise,” with others pointing out how troubling the discourse feels, so barely coded as to be outright racist.

Most of this discourse seems to have started from TikTok videos speculating that Kim Kardashian, along with her sister Khloé, have gotten “BBL reductions.” Back in December, i-D ran a piece asking “Are We Witnessing the End of the BBL Era?” with a Dazed article following shortly thereafter, attempting to answer the question with the claim that the current aesthetic runs more “heroin chic,” citing studies showing that anorexia is once again on the rise. It’s a shift tied to various trends in sub-culture that the artist Precious Okoyomon has termed “anorexic white supremacy.”

Fashion influences the political-cultural sphere in a covert manner, and not the other way around. Which is why outwardly political garments (or art for that matter) are often seen as bad or try-hard. (Twitter’s roasting of “Peg the Patriarchy” or “Tax the Rich” as messages at the 2021 Met Gala reveal a sphere wherein layers of irony read and earnestness gets clocked as cringe.)

In a piece for The New Inquiry, Charlie Markbreiter writes, “Cringe is the gap between how others see you and how you want to be seen, opening up the tricky ambiguities of how you see yourself.”

Markbeiter argues that cringe functions as a form of social control, the term gaining traction as a descriptor for social justice warriors: “The critics had a point: for the post-woke leftists, SJWs are cringe because of the gap between what they think they want (justice) and what they actually want (narcissistic supply).” The piece explains that this is meant to be the gotcha moment, in which the SJW is revealed as perpetuating the neoliberal individualism they claim to be fighting against, i.e.: having opinions to get likes, going too far to get your attention.

The want for answers is inevitable when the return of low-rise provokes an emotional response in those who lived through the early aughts heyday of normalized eating disorders and a pop culture that chastised women for their appearance. It was in 2008, as Paris Hilton’s fame was beginning to decline and Kim’s rose, that Hilton called into a radio show to say that Kim’s butt was “disgusting,” and that she “wouldn’t want it,” likening Kim’s body to “cottage cheese stuffed in a trash bag.” (Hilton apologized for the remark less than 24 hours later.)

Perhaps the updated part of the Y2K trend isn’t the silhouette or the styling as much as the ways that these views can be hinted at, in poking fun at BBLs at a runway show, for instance.

In Fearing the Black Body, sociologist Sabrina Strings looks at the growth of the slave trade, in order to articulate how European whites became obsessed with dieting and body size, searching for aspects of racial identity that went beyond skin color to build the argument for a “superior race” with the idea that white culture was one of rational self-control. Strings looks at the ways in which previous notions of European feminine beauty favored “softer bodies”; then came the type of articles such as those found in 19th-century magazines like Harper’s Bazaar, that advised American women to eat as little as possible, invoking Christian ideals alongside innuendos of racial superiority, which were expressed in no uncertain terms. Strings traces this history to the ways that modern media continually push the culture that Okoyomon termed anorexic white supremacy.

Regardless of one’s thoughts on the Kardashians’ global empire, the suddenness with which the family changed body standards that the fashion industry had deeply instilled in the culture is striking — if fashion is like politics, beauty is closer to sports, where rules are slower to change. Yet this sudden shift couldn’t have happened in a bubble. Kim Kardashian may have had the most visible BBL worldwide, but in talking about her “aesthetic,” much has been said about the way the Kardashians have taken from Black culture in order to make their collective $2.2 billion.

Trends start from the margins, in part, because of the perceived “freedom” of those living in more precarious situations, through the eyes of those who are more comfortable, bored. Those who will never be as rich as the Kardashians but who live without much awareness of the construction of the systems that benefit them. The celebration of “the end of the BBL era” might try to pass as a discourse about impossible beauty standards or else as a dig at Kim Kardashian — but to let the conversation end there is to essentially accept the pretense that the Kardashians truly earned their billion dollar empire, via the American fantasy of hard work alone. This is a distortion wherein, by being linked to the Kardashian brand, aspects of Black culture can be written off as a trend: The hypebeasts look for what’s next while white supremacy propels its sense of itself as timeless.

To celebrate the supposed “end of the BBL” is synonymous with the desire to kill the ways in which Black women, especially Black trans women, and especially Black trans sex workers, have shaped the culture and were co-oopted by the mainstream. It’s a sort of cultural regentrification, wherein the figures who built a culture while fighting for survival cannot themselves be absorbed into dominant culture; they are too radical, too queer, too willing to tell the truth about the system that will not change to accommodate them. Fashion facilitates a replacement process. What’s left is only a wash of credibility, if you know you know.

Kardashians aside, the BBL never quite caught on with A-list names, save rappers like Cardi B and Nicki Minaj. One reason for this is it isn’t an operation that most doctors will perform on women who keep the consistently thin (or underweight) body type that Hollywood has long required of its starlets. The BBL is a fat transfer operation, which by nature favors a body type with enough weight for fat to be transferred to the patient’s desired parts of the body, and enough of it so that the transfer will “keep” after the weight-loss associated with the recovery — that is, weeks of lying on your stomach, no working out, and sleeping for the first week or two, depending on whether you can score enough painkillers after the now tightly controlled supply that doctors in the United States are legally allowed to prescribe runs out.

Where the BBL most caught on was in the sex industry, which is where many other gone-mainstream beauty trends (lip injections, hair extensions, and acrylic nails — to name a few of them) also got their start. For sex workers, who are often paid for looking vaguely “exotic,” though still white passing, being at the forefront of beauty trends might be the best way to transcend class or, at least, to make ends meet. It isn’t hard to imagine that for sex workers who were never thin or who had aged out of easy thinness, the arrival of the BBL could have felt like a godsend.

So why is this supposed “end of the BBL” trending now? If we are living in an era, as Charlie Markbreiter offers in the piece on “cringe,” of celebrated post-wokeness, post-leftism, and horseshoe’d Trumpisms, it follows that this new era of social conservatism is reactionary to the June 2020 riots. As the riots gave way to parades, and information about where demonstrations were going down gave way to influencers posting black squares on their profiles, an entire uprising dissolved, fearing association with “cringe.” But if “woke scolds” use cancellation to police each other — compelling minor influencers to clog social media feeds with empty political messaging — then the post-woke use fear of being “cringe” as a social control. It squares that both might end up at the same place, serving a centrist agenda.

In the fast-fashion, digital age, nostalgia cycles continue to move at increasingly rapid rates, with vintage trends closing in on such nearer and nearer pasts, that it’s difficult to forecast what we could possibly be nostalgic for next.

While Y2K has been on the radar, this past year has seen an uptick in the prediction of the Herve Leger bandage dress being the next trend to resurface. Are we now post-cringe? Either we’ve reached a stage of culture in which all past trends are rehappening at once, in which we are beyond cringe, or else Miu Miu has already fallen behind.

There may be a socially conservative current with enough self-perceived cachet that it would dare to proclaim the BBL is over, but that doesn’t mean it’s true. In fashion, like politics, there is never only one current. The answer isn’t as simple as refusing to engage in trends, since trends will often affect an inescapable breadth of consumer goods and, all the while, culture keeps moving and cycling. It is as simple, however, as being able to know your enemies. The side opposing social conservatism is by its nature more fun, more hedonistic, more radical. To hear “the end of the BBL” is to sense shots fired from one side of the culture, yet I trust that when platforms appear, there will be even more creative and nuanced ways to say f*ck you back.

This article was originally published on