Entertainment

Paris Hilton's "Stars Are Blind" At 15 Is Perfect Vapid Bliss

The socialite’s debut single was so fundamentally unconcerned with coming across as smart or original that it wound up being both.

The first time I remember hearing “Stars Are Blind,” I was in the back seat of my older sister’s high school car, a white Honda Civic with a pink flower decal stuck to its bumper.

It might not have been my literal first listen — it’s plausible that I’d already caught a snippet on KISS-FM or half-watched the contrast-heavy video on VH1 while channel surfing in the middle of the night. But it’s this otherwise unremarkable afternoon car ride with my sister and her best friend, both 18 and about to graduate, that I continue to associate with the reggae-inspired earworm, which was released 15 years ago this week.

I don’t remember where we were going, only that it was warm outside, summer so close we could practically feel it, like the underground vibrations of an Amtrak train barreling toward a station. I was freshly 16, and though I’d secured a learner’s permit and a part-time job bagging groceries at a local supermarket, I still relied on my sister to shuttle me around, often tagging along on inane errands just to get out of the house for a couple of hours.

When “Stars Are Blind” came on the radio, my sister and her friend screamed, one of them reaching down to crank the volume. I can’t remember my own knee-jerk reaction to the song’s opening groove — which, I realize now, recalls the midtempo intro of “Straight to Hell” by The Clash, the Combat Rock single that M.I.A. iconically sampled a couple of summers later. I probably slouched in my seat and pantomimed disinterest, committed to a pre-poptimist belief that anything overproduced was inherently embarrassing. Weirdly, though, it was this hyper-fabricated quality that eventually won me over — that day in the car and on every subsequent listen over the past decade and a half, of which there have been many.

Sung in Paris’ thin register, pitch-corrected right up to the edge of anonymity, the lyrics of “Stars Are Blind” urge a crush to act on their romantic impulses, even if it means going against what is predestined by the cosmos: “Even though the gods are crazy / even though the stars are blind / if you show me real love baby / I’ll show you mine.” This flirty and vaguely libertarian narrative is paired with a swaying melody that sounds more or less identical to “Kingston Town” by UB40, the popular late-’80s cover of the Lord Creator original from 1970. (A plagiarism lawsuit filed by UB40’s label, Sparta Florida Music Group, was apparently settled out of court in 2009.) The finished product sounded audaciously carefree, so fundamentally unconcerned with coming across as smart or original that it wound up being both. It’s part sweat-slicked summer banger, part uncanny art object — a plastic-wrapped descendant of Aqua’s “Barbie Girl” and accidental ancestor to the subversive gloss of the PC Music catalog.

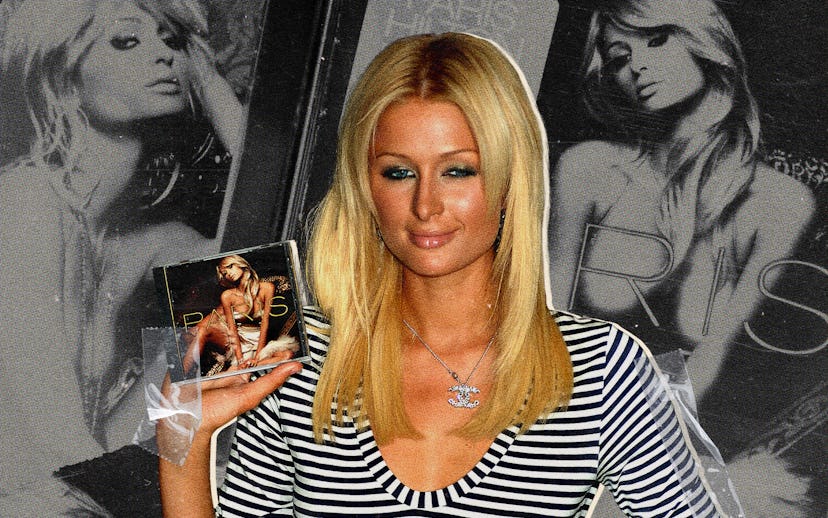

The provenance of “Stars Are Blind” begins with Lady Gaga and Sia collaborator Fernando Garibay, who sketched out a demo version with Gwen Stefani in mind to sing it. Part of me understands where he was coming from; the No Doubt frontwoman’s hypothetical interpretation would have likely landed somewhere between the stoner sass of “Sunday Morning” and the ultra-cinematic romance of “Cool.” But because Stefani was busy prepping for a new baby, Garibay wound up pitching the demo to Paris Hilton’s A&R at Warner Bros. Records, who swiftly locked it down as the polarizing party girl’s debut single — the general public’s official introduction to Paris Hilton, recording artist.

“It’s part sweat-slicked summer banger, part uncanny art object”

In a 2013 video interview, Paris reflected on hearing “Stars Are Blind” in the wild for the first time. “I was in the car just driving and all of a sudden it started coming on the radio and I was so happy,” Paris explained in the clip. “I was driving in Malibu … I remember that, I’ll never forget … just singing along and driving in my convertible down the road.” It’s telling that my most visceral memory of the track is similarly windswept and generic; “Stars Are Blind” is a designer drug, a serotonin-blasted relic from an era when you could hop in the car, switch on pop radio, and chase all your cares away. For 2006 me — a closeted queer sophomore from small-town New England, 3,000 miles from Malibu and too self-loathing to admit the extent of my fascination with post-Laguna Beach femininity — the advanced level of escapism offered by “Stars Are Blind” was borderline medicinal, even if I only recognized it in retrospect.

It doesn’t surprise me that the finger-picked tune of Taylor Swift’s 2019 tearjerker “Soon You’ll Get Better” echoes “Stars Are Blind,” nor that millennial filmmaker Emerald Fennell wrote the song into her Oscar-winning screenplay for Promising Young Woman; the track’s cultural footprint is bigger than its early mixed reviews and moderate chart performance might have suggested. Swift’s ballad is about her mother’s battle with cancer, and so this melodic allusion to “Stars Are Blind,” whether knowing or entirely subconscious, suggests nostalgia for less fraught times. The Promising Young Woman scene is deceptively joyful, a falling-in-love montage that develops an unsettling quality in light of a third-act twist. That “Stars Are Blind” is flexible enough to straddle all of these moods is a testament to its particular power, to its durability as a vessel for both meaning and memory.

My sister’s Honda Civic was a world unto itself, a sacred space protected from the critical glares of teachers and bullies, from parental pressure and report-card anxiety. “Stars Are Blind” is that untroubled feeling in musical form, and embracing its formulaic hooks as a young person felt like an act of agency or a kind of rebellion — willingly choosing, for three minutes and 56 seconds at a time, to act as vapid and boy-crazy as everyone probably assumed you were anyway. To listen now is to return to that windows-down sanctuary — long tangles of shiny hair billowing in yellow light, air that smells of berry lip gloss and Hollister perfume, a synthetic-sounding voice on the radio, singing about star-crossed love.