Culture

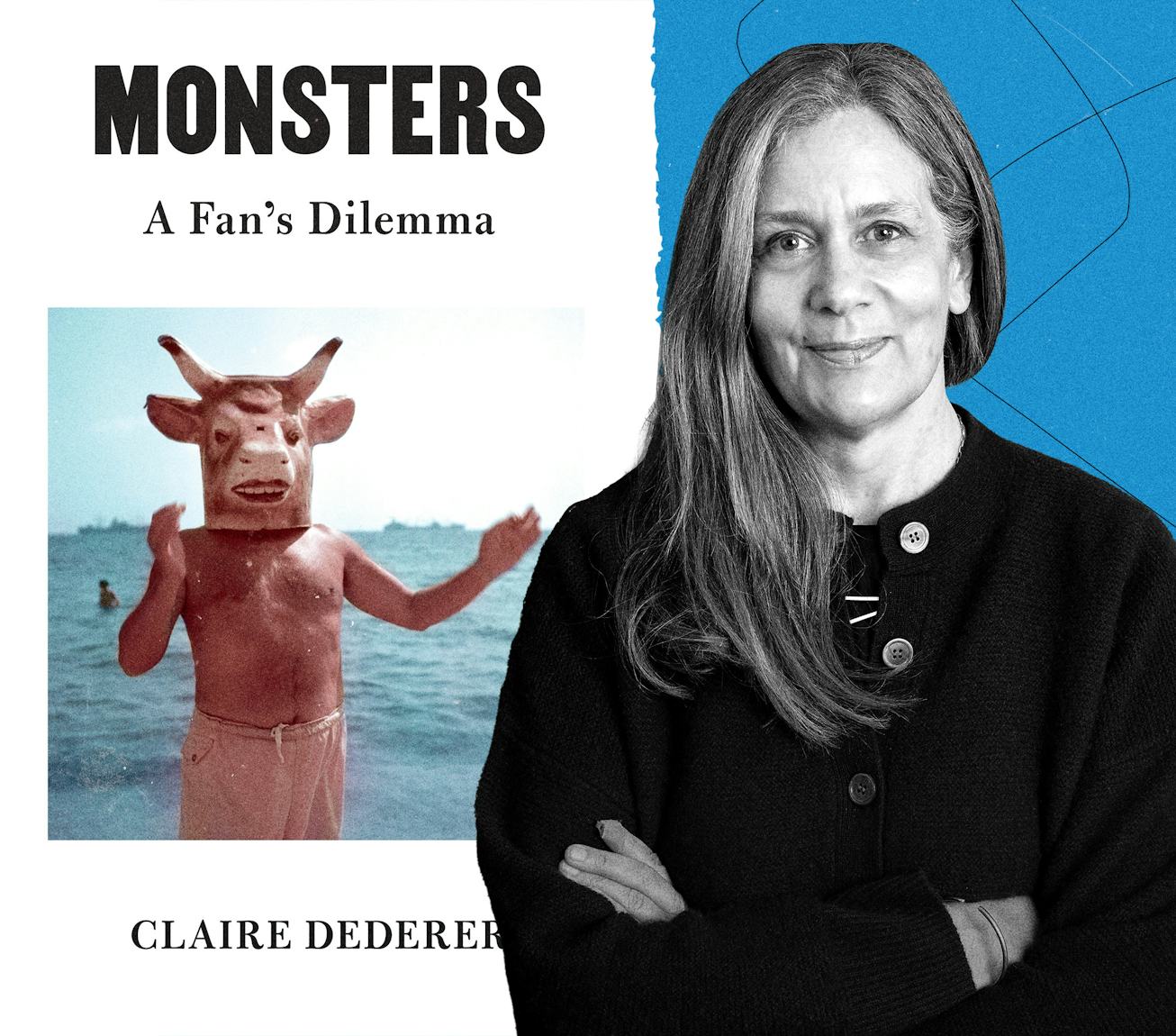

Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma Explores The Gray Area Of Bad Artists

In Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, Claire Dederer’s only absolute is a love of art.

When I think about how the monstrous acts of men have affected my consumption and love of the art they made, I think about a scene in High Fidelity, the tragically short-lived television adaptation of the film of the same title, which aired in Hulu in 2020 and stars Zoë Kravitz the Crown Heights record store owner Rob, in a remarkably self-effacing performance.

In the show’s second episode, a blonde twenty-something is trying to buy Michael Jackson’s 1979 record Off The Wall, which was produced by Quincy Jones, for her boyfriend. Cherise, who works at the store, refuses to sell it to her, saying she is someone "who clearly has never been on the internet before."

"How does it benefit society to hold Quincy's genius hostage just because the dude who sang over his sh*t ended up being a full-blown child molester?" Rob responds. “Alleged,” the blonde girl says. Rob bows out and leaves her employees to play rock, paper, scissors to decide the record’s fate. Whether or not they sell it is the least interesting thing about this scene.

There have always been monstrous men. In 2017, the #MeToo movement, which was founded by Tarana Burke in 2006, exploded, offering up the Internet as a public place to talk about them.

Claire Dederer had been preoccupied with the topic for a few years already. She started writing Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, an extraordinary and ambitious study of the slippery problems of biography when it comes to consuming art, in 2014.

For Dederer, few things are as sacred as art. She wasn’t so quick to toss her Woody Allen books in the Little Free Libraries in her Pacific Northwest neighborhood. It is rare, she explains, to feel truly moved, and it is a complicated decision to cast aside people whose work truly moves us.

“That idea of looking at something in as clear-eyed a way as possible, that's how I want to look at art, but it's also what the book is trying to do,” Dederer tells NYLON. “The book is not meant to be prescriptive. It is meant to be descriptive of what happens inside us as we, or me, a person, as I navigate this problem.”

The last several years have sometimes felt, to me, like one impossible math problem: weighing out the math of watching a Roman Polanski film; laughing at a Louis C.K. joke; or enjoying a Picasso painting in the wake of revelations around acts of monstrosity. Dederer encourages herself to avoid the “we,” so I will say that I often feel tempted to throw my hands up and abdicate responsibility, to say “It’s complicated!” and leave it at that.

But Dederer dove in headfirst – and what she found is a gray area that neoliberalism generally tries to avoid. It’s a book that’s not afraid to say, “I don’t know,” written by an author who isn’t afraid of her mind changing as she unpacks everything from Woody Allen’s Manhattan to Vladimir Nobokov’s Lolita to J.K. Rowling, full stop. Most notably, the book’s greatest feat is in its refusal to spit out any absolutes. It will not give you an answer to the math equation that plagues a lot of us: “I wished someone would invent an online calculator — the user would enter the name of an artist, whereupon the calculator would assess the heinousness of the crime versus the greatness of the art and spit out a verdict,” Dederer writes. “You could or could not consume the work of this artist. A calculator is laughable, unthinkable.”

Dederer doesn’t tell us what the outcomes of our own equations should be; she tells us to throw the math problem out entirely. After all, these are issues of feeling. Dederer doesn’t want anything, ultimately, to affect her ability to consume and appreciate art, stained and all. “We're lucky,” Dederer says, “to love something.”

NYLON spoke with Dederer about how she is protecting her relationship with art now, and why she thinks the number one artist that people ask for permission to still love is David Bowie.

MONSTERS is out on Penguin now.

How do you think that writing has changed you or how you look at art now?

Because of this special role I now have as somebody who's thought about this really hard for years, I feel like I have almost a more intensified experience of what we all have, which is I have this feeling of: I want to protect my experience of art from what I know. This idea of biography falls on our heads all day long. We can't escape it. We're constantly experiencing art within the context of biography. In some ways, the way that I use the word biography in the book is almost as a perfect synonym for the internet, because they're so one and the same in my mind. I think that that relationship that we have with the internet and biography is unavoidable, that's the problem.

But coming out of the book, what I almost have is a sense of urgency about protecting my relationship with art, not just from biography, but from my own performance of consumption, my own performance of identification with the victims. These things don't really help anyone, per se. It's important to listen to victims, but that's different from consuming art in a performative way. I guess what I'm thinking about is the idea of: how do I protect my art love from being public, and how do I move through the world in a way that is allowing things to happen? I use this line from Shirley Hazzard in the epigraph, where I talk about the submission required by art. I think oftentimes that that's my desire, is to be more inside that submission. Where I'm not performing my reaction to it, or constantly measuring it against the biography, but then I'm allowing myself to be moved in that way.

Do you ever want to just totally disassociate yourself from the conversation? Do you feel like that's something that you would even be able to do at this point?

I definitely think it's something I can do, and yes, I'm happy to have the conversation insofar as it then becomes a useful way to look at the problem for other people. But I also feel that I do have the power to escape it, I do have the power to listen to music or go to the museum or read a book and undergo that submission.

I went to the Chicago Art Institute the other day and I sort of jogged through the Picasso rooms. I was on my way to look at a special exhibition of Dalí's work there. I walked through Dalí and I just couldn't escape the conversation while I was in that room, about history, about biography. I left, and I went and wandered around a bunch of other galleries and was able to move from this more determined conversation into that more porous, submissive, transported kind of experience that real looking actually involves.

I always think about this book by Lawrence Weschler about the minimalist artist Robert Irwin. The title of the book is something Irwin once said, which is “Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees.” I feel like that's so much the ideal state. I think that doesn't mean we ignore the biography, I think that it's okay to have a complicated seeing. I think it's okay to know, I think it's good to listen to people when they say something awful has happened, and then also, it's good to try to really apprehend the work as it is.

As an artist yourself, there is that chapter called “Am I A Monster?” I'm curious why you wanted to interrogate your own monstrosity.

I'm going to say an absolute thing, which is very unlike me, but I don't think that you can be a good memoirist and not self-indict. I think that if you're writing about something, or looking at a topic as a memoirist, you have to turn the pointing finger back at yourself. It was a very natural place for me to go as somebody who’s written a memoir. I would say that there's a couple intellectual and political projects in the book, and one of them is to subvert the idea of critical authority and carry a banner for subjectivity, to carry a banner for the idea that we're all writing out of our own subjectivity. It was really important for me that the book reflect that subjectivity in its form, in its structure. I wanted to reinforce that idea in the way the book itself was made, and so that was one of the other reasons I came back to “Am I A Monster?”

The fact that so many people asked: “Can I still listen to Bowie?” really stuck with me. Can you talk about the role of the fan who gets something so visceral out of someone’s art?

I think he does feel so important in terms of that mysterious thing that happens when you're very young, where music simultaneously makes you more your individual self, and also makes you part of a group, whether real or imagined. It's this simultaneous affirmation of your solo identity, and then a belonging to this race of aliens that he seems to belong to. He really captures that, and I think that's why he feels so important to people.

Something about those synapses firing when you're young makes it so much harder to let go of something that you deeply love and feel seen by.

It's interesting to think about this idea that maybe we let go of those things when we're older because we're just hanging onto nostalgia. At the same time, maybe the young have a different responsibility, because they are in the throes of this often very painful identity formation, and they need the help of art. They feel things so deeply; they need art, in a way that honestly I feel is a model for how I want my relationship to art to be, because they are undergoing that submission that Shirley Hazzard's talking about. And to me, that's a dream to be in that state. When I find myself in that state as a middle-aged person, I'm thrilled.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.