Culture

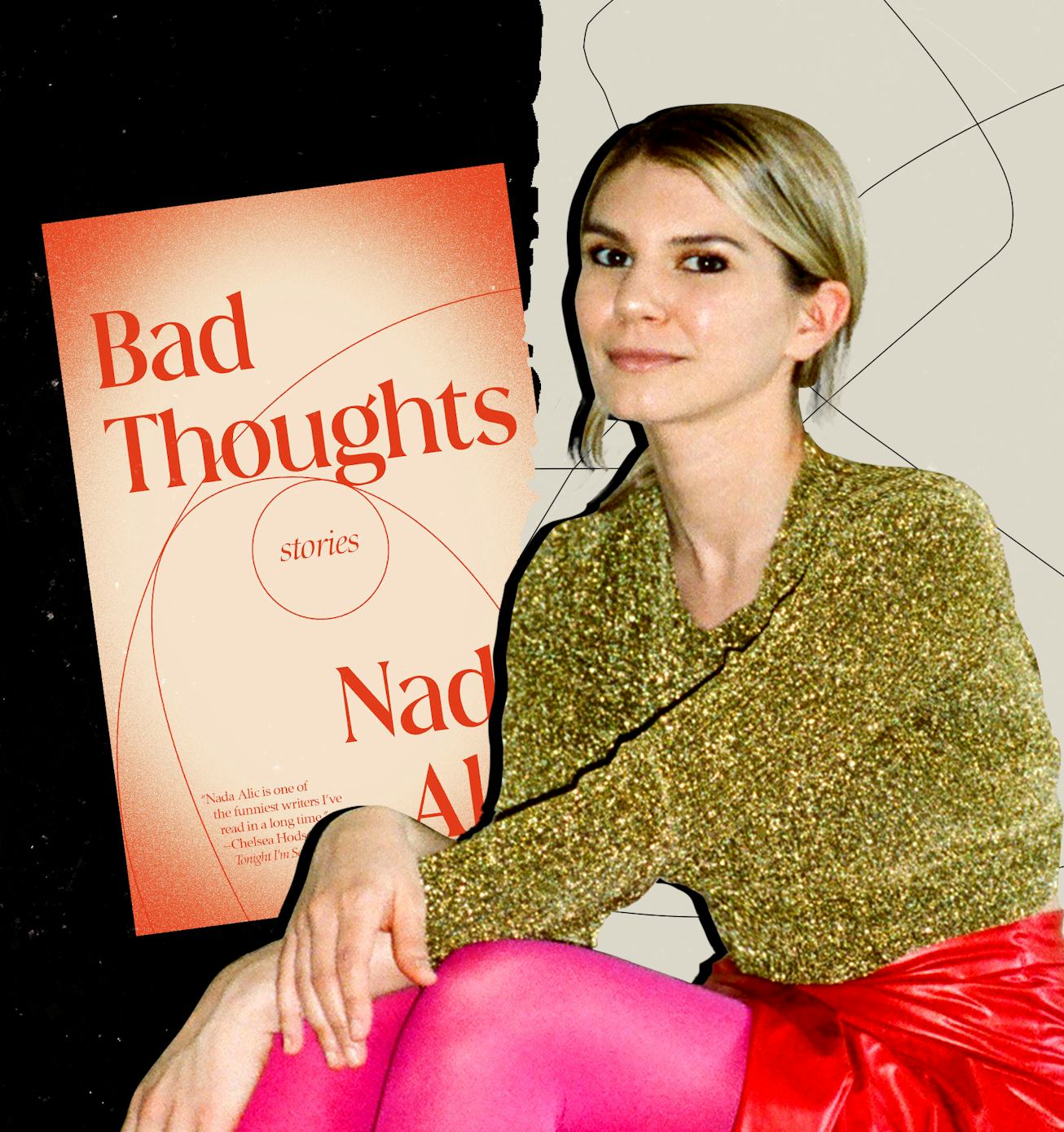

In Bad Thoughts, Nada Alic Embraces The Humiliation of Being Human

It makes you wonder why we’re so judgmental about ourselves, or whether such a thing as a “bad” thought even exists.

“Being alive is humiliating,” Nada Alic tells me during our phone call earlier this month. We’re talking about the slap of embarrassment that occurs when you say goodbye to someone on the street and walk the same way as them, or when you realize nobody at the dinner party is listening to your story, the tiny moments that affirm you, however awkwardly, of your own humanity. “It doesn’t take much to have a person absolutely unravel.”

It’s this acknowledgement of everyday humiliations that gives Alic’s debut short story collection Bad Thoughts, a soothing effect, like a spiritual salve for our broken brains. Alic takes the idea of a taboo thought and exposes how normal, even boring, it is, remaking the idea of a “bad” thought as what it actually is: just a part of being human.

Reading about the women in Alic’s stories is akin to calling a good friend to tell them something embarrassing you said only to find out they said something worse. The stories follow girlfriends of rockstars, wellness junkies, reality TV hopefuls, and nobodies, all who possess thoughts they’d rather conceal. In one story, a woman changes her whole life while relentlessly checking her email to see if she’s accepted into a writing retreat she thinks will change her life. In another, a woman’s sense of self is upended while she waits at home alone while her boyfriend is on tour. In another, a woman is preoccupied with a desire to touch a man’s penis over his pants.

“They all looked so vulnerable, so up for grabs; concealed only by a thin layer of fabric. I imagined them as windchimes waiting to be struck,” Alic writes. “The impulse wasn’t sexual, it was destructive. I just stood there, not touching anyone’s penis, quietly frightened by who I was and what I was capable of.”

It makes you wonder why we’re so judgmental about ourselves, or whether such a thing as a “bad” thought even exists. Reading it is gives you the simultaneous hyper-awareness, embarrassment and eventual acceptance that comes from staring at yourself in the mirror for too long.

Talking to Alic gives the same salve. While waiting for our interview to begin (I didn’t know if she was going to call me, or vice versa — a procedural detail of our embarrassing lives that we both didn’t think to coordinate), I became so preoccupied with how dirty my phone was that I felt compelled to tell her. We spend a long time discussing disgusting phone cases, how we prefer voice memos to text messages, and how everything is giving us carpal tunnel.

“There’s also a lot of comedy in pointing out the ways in which we fail at performance,” Alic says. “I’m always looking behind the curtain and behind someone’s whole appeal, especially in LA, everyone presents as this idealized version of themselves, but there are all these micro humiliations we all face throughout our days.”

Part of what drives that instinct for her to help people feel less strange is her own outsider status in the publishing world. Alic, who got her start writing about music on Tumblr, was born to two Croatian immigrants who worked all the time. She didn’t grow up with books in the house, get an MFA or have industry connections. She would write on the weekends when she wasn’t commuting an hour for her day job before eventually quitting the job to make herself finish the book.

For a few years, she also made zines with her best friend, the artist Andrea Nakhla. She would do readings in LA where she would read an earlier version of Bad Thoughts, mostly funny aphorisms about life that aren’t unlike Tweets that she included in the book: “I feel generous and saintly whenever I let a man tell me what my name means,” or “My dream podcast is just overbearing my boyfriend talk about me in the other room,” to name a few.

Eventually she sold the book, and thanks to its sharp prose, compelling characters and Alic’s creative marketing, which included everything from artful book trailers, to t-shirts that were actually cute, Bad Thoughts has been getting a considerable bit of attention now. Ahead of the book’s release, NYLON spoke with Alic about women who don’t want to grow up, how Instagram therapy graphics have gone too far, and why we’re all so embarrassed all the time.

Bad Thoughts is out now on Vintage.

What I love the most about this book is how fun it is to read. I’m never bored. The voice is that of a real person: funny and colloquial. It's how people talk when they're at their most interesting, or their worst. What do you think influences your voice?

I grew up watching standup and being really into comedy. I really love novels that are more interior and personal, and I always like it when a book considers me as the reader, so I purposefully try to use the language I thought these characters would use. I’m not trying to impress you with my intellect. I just want to be really generous and inviting and it’s the stuff that I really like to read, so I wanted to write something that was a little more satirical and humorous.

I like that idea of you as a writer you don’t have anything to prove. That feels like an exercise in healthy ego loss.

We’re so inundated with people constantly performing an intellectual or academic or performing these versions of themselves and I think one of the big themes of the book is performance. I wanted to get behind the curtain a little bit. I’m so obsessed with the ways that people perform and when they slip up and reveal their humanity. We live in a culture obsessed with performance. I was revisiting Sheila Heti’s novel Pure Color and she was talking about living at the end of the first draft of existence and we’re just living at the end of the credits of a movie and everyone wants to see their name up on screen. I want to keep shedding a light on our humanity and the parts of ourselves that are a little more embarrassing, to neutralize and normalize that.

That’s what Bad Thoughts does, it takes the idea of a bad, strange, or taboo thought and makes it extremely normal and not actually bad – but just a part of being human.

Honestly, my whole goal in life is to figure out ways to transmute shame into humor. I think so much of ourselves is incompatible with these versions we’re projecting ourselves out into the world and it’s like, well, what do we do with that? For me, one way to reconcile that is taking those dark parts and making them funny or normalizing them.

There are a few different ways you can do that as an artist. Humor is kind of like the lens through which I see the world and the absurdity of it. It has this sort of this diffusing effect. I’ve been reading Ottessa Moshfegh’s book [Lapvona] and the way she does it is through the grotesque, which is another way to integrate that darkness, but it’s like on a whole other level. With her, she’s getting us to face the horrors in life in order to take the power away from it. She’s not trying to entertain or anesthetize, she’s trying to wake you up, and she’s so brilliant. I can’t really do that, but my version is maybe a softer way of mining the dark parts of the psyche.

To go off Ottessa, books about messy women in particular are having a moment, which girls on #BookTok can’t get enough of: the Ottessa, Sally Rooney, Fleabag moment. What do you think about that? Does your book fall into that canon?

Yeah, it rubs up against the other end of the pendulum, which is that really polished, sanitized version that everyone is projecting online of perfection. I think that’s why it can be both very intriguing, but also triggering to some people to be forced to see those imperfections displayed through these characters. I feel like it’s starting to change even with TikTok culture, even with younger people being accepting of the full spectrum of humanity. There’s also a lot of comedy in pointing out the ways in which we fail at performance. I’m always looking behind the curtain and behind someone’s whole appeal, especially in LA, everyone presents as this idealized version of themselves, but there are all these micro humiliations we all face throughout our days. Maybe you say goodbye to someone and then you start walking in the same direction as them. The other day the barista forgot my order, and I was, like, regressing into this wounded child. It doesn’t take much to have a person absolutely unravel. Like those moments I'm so obsessed with, you’re just cutting through the performance and revealing our fallibility and our immortality. And I love calling that out because I cannot stand pretending. I can’t even really do small talk or anything.

Do you feel like writing this book has made you change how you view yourself or those own “shameful” thoughts? Has it changed your perception of yourself at all?

Absolutely, I think it was kind of therapeutic for me to embody these characters, some of which are obviously so exaggerated, but they contain some part of myself. I was able to lark as a total asshole, or a really obsessive girl, and I’ve been all those versions of myself. I’m so obsessed like everyone else is with therapy and self help and spirituality, and those are other containers that help give language to those darker aspects of myself. But at the same time you get a lot of spiritual materialism and people trying to repackage the divine or these parts of ourselves that are accessible that we can figure out on our own. I see that a lot in LA and I see that a lot on Instagram, too, and in a weird way it really offends me, because it’s performance leaking into sacred spaces. I'm like “Oh no, no, no, you can’t exploit that.” The idea that you have to buy a mantra to meditate or that kind of thing. Living in America, there is such a crossover between capitalism and therapy and spirituality.

“But there are things in your life that you’re like, ‘I want to hear that other people have thought this terrible thing, so I feel less bad.’ It does sort of give you this instant relief – that’s the throughline in the book, too.”

The Instagram therapy graphics have gotten completely out of control. At a certain point my Explore page was like: “Four ways your mother abandoned you” and “five ways you’re self-sabotaging.” As if there’s some shortcut.

As if there’s even a version you could arrive at that’s the perfected version of yourself. It’s just a process. I feel like whatever I say is just an accumulation of the last five podcasts I listened to. I’ll be like, “integrating my shadow.” I learned that phrase and I’m like that’s my whole identity now, so I have to push back against all my beliefs and be like, “Maybe I’m wrong about everything and that’s why I included that epigraph from Sarah Manguso about pathologizing every human quirk.” [“Instead of pathologizing every human quirk, we should say, By the grace of this behavior, this individual has found it possible to continue.”— Sarah Manguso, 300 Arguments]. I just love that because it does feel like on the one hand, it sort of goes back to not everything is wholly good or wholly bad. It’s opened up this whole language of trauma and things that have been really beneficial and have helped me so much, but then maybe there’s a tipping point where it becomes unproductive to identify with too many of these things. The categorization is almost limiting. Not everybody is able to dive into the deep end and do mushrooms and, like, confront the divine directly, which I totally get. People need a touchpoint or a framework for some of this stuff.

Do you have a favorite character in the book?

Wow, no one’s asked me that yet. I mean they’re all little aspects of myself. “My New Life,” that first story, sets the tone for everything. It’s about a woman who has an unnameable restlessness or agitation kind of leading her to act out and she doesn’t really understand herself and then she’s got this charismatic best friend who comes in and just forgives her of her worst offenses. I think that sort of has mirrored my relationship with my own best friend, where I will think or do something terrible and I’ll immediately call her so that she can kind of be like, “Oh that’s not so bad, I do that, too.” But it’s also not productive either because I’m always seeking absolution through her and obviously we've grown up a little bit since then and we’re less terrible people. But there are things in your life that you’re like, “I want to hear that other people have thought this terrible thing, so I feel less bad.” It does sort of give you this instant relief – that’s the throughline in the book, too. I just wrote this essay that’s going to be in Harper’s Bazaar about the “puella aetern” archetype, the female Peter Pan. So Peter Pan is a boy, right? But nobody hears about the woman version, and she is real, so this sort of “puella” archetype are these women who resist adulthood and pass through these big threshold moments and cling to their youth in a way. They’re really interesting characters to me, so I think that one sets the tone for the book.

Does the proliferation of this messy woman protagonist who isn’t really ready to grow up feel at all like a reaction to the girlboss era, a time when we really expected women to grow up, and fast?

Right, “lean in,” even though most of us just want to, like, lie down. It is sort of in response to that. There’s a place for women who don’t fit into this aspirational, super productive lifestyle. I think that even those women have repressed parts of themselves. But it is becoming more of a mainstream thing. We see it a lot more now in culture. It will be interesting to see where the evolution of art and this specific character goes now that we've all sort of accepted and celebrated her as well.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.