Culture

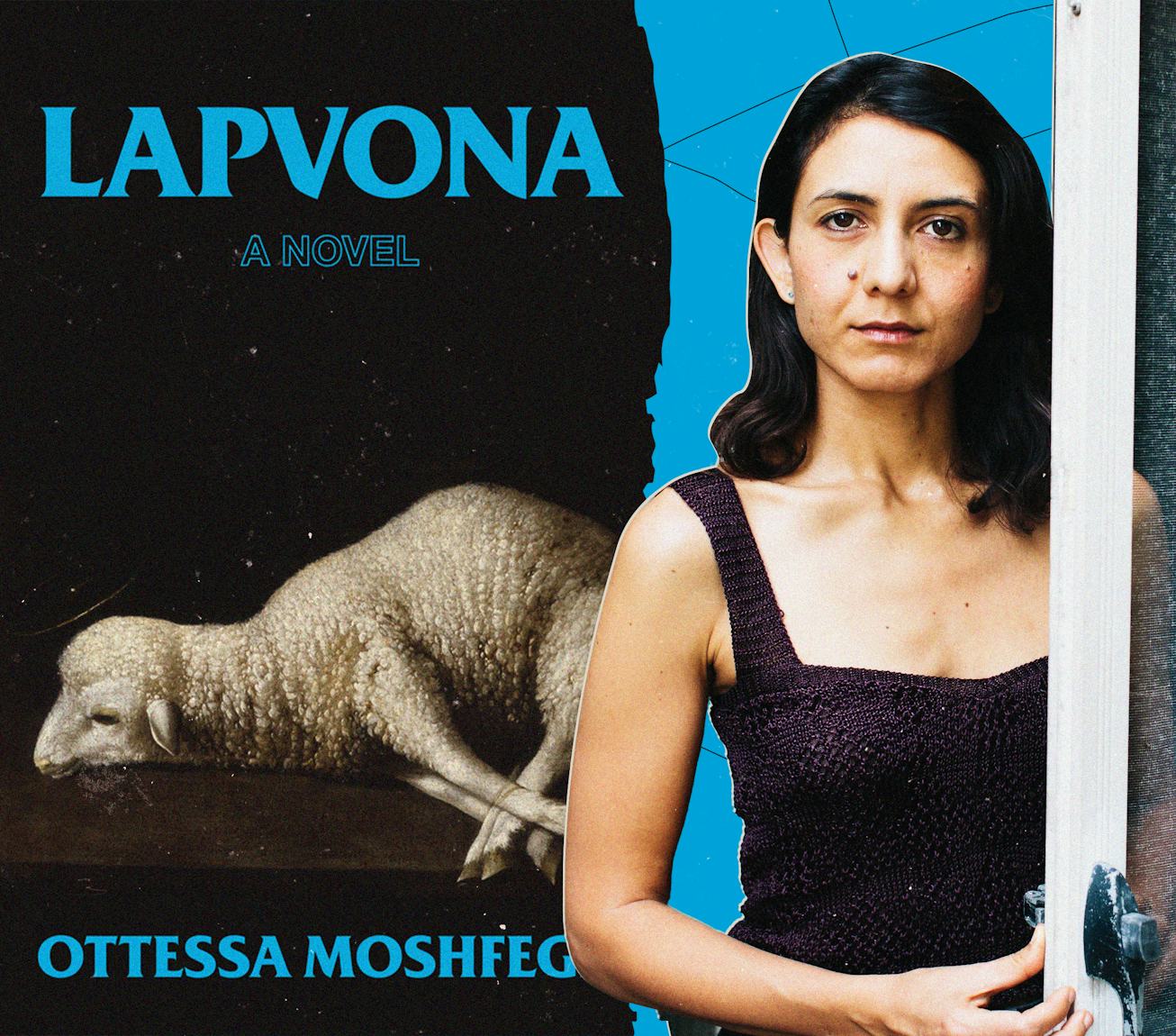

Lapvona: Ottessa Moshfegh’s Depraved Medieval Times

With Lapvona, Ottessa Moshfegh has purged her obsession with the grotesque.

Lapvona, the latest novel from Ottessa Moshfegh, is her most grotesque book yet. It’s also the most important one she’s written for herself, she tells me over Zoom from her home in Los Angeles, which she says is made of stones from a “ruined church” and describes as “very church-y.” Moshfegh’s sanctified home is a casually fitting detail for an author who has a cult-like following, whether its from literary critics, the devotees of #booktok, fashion designer Maryam Nassir Zadeh, or the hordes of young people, who, at any given time are trading a copy of My Year of Rest and Relaxation between chipped manicured hands. A recent New York Magazine feature included the headline “Ottessa Is Praying For Us” with an illustration of her as a saint.

“With Lapvona, there is something that I hope to have processed, which is a real obsession with…” she pauses. “I guess, morbid reflection. And I think it’s part of the human experience. I have absolutely no shame or embarrassment about that and I think people don’t like it because it’s disturbing and like, good on you…But I did feel like Lapvona was a bit of giving something away, and not just in the putting to bed my fascination with morbid sh*t, but also paving a new way into looking at storytelling.”

Moshfegh fans are no strangers to the ugly, but they might be utterly shocked at how far she takes her excavation of the grotesque and monstrous in Lapvona. As it turns out, the horror, both of body and mind, in novels like Eileen and My Year of Rest and Relaxation were just the appetizer. Lapvona is dinner, and surprise! You’re eating your neighbor’s corpse. There’s barely any applesauce for the medicine, and the applesauce available is, in fact, rotten.

Everything in Lapvona, a folk horror story set in a Medieval fiefdom of the same name that revolves around a motley crew of characters undergoing unimaginable circumstances, is dialed up: Moshfegh’s obsession with the grotesque, her demented sense of humor, and her ferocious wit. By page 21, when Marek, a deformed, orphaned child of incest starts sucking on the teats of lambs, I knew Lapvona was going to be a different kind of book, one more deranged than anything she’d written before. It’s a feat for the author who has been much lauded for her penchant for writing about the monstrosity that’s in all of us. “He pushed the babes away and put his mouth to the sheep’s teat and sucked until he felt sick,” she writes. “He felt this was his right as a child of God.”

Later, a nun whose tongue has been cut out is raped, people die of starvation, regurgitate fingernails after eating their neighbors and smoke weed out of a pipe made from their bones. All of this to say, the world of Lapvona is objectively hilarious, verging on camp. The book’s dedication is, after all, a Demi Lovato quote: “I feel stupid when I pray.” There’s Ina, a blind wet nurse who gets her vision back when she nurses grown men, that is, until she finds a permanent replacement in the eyes of the dead queen’s horse. There’s Lisbeth, a servant only permitted to eat cabbage who is humiliated when the developmentally stunted Lord Villiam commands she eat a single grape that’s been rubbed on the butt of the boy who killed her forbidden love. “Excrement,” Villiam asks. “Is that like sacrament?”

“I did feel like Lapvona was a bit of giving something away, and not just in the putting to bed my fascination with morbid sh*t, but also paving a new way into looking at storytelling.”

It’s tempting to think of Lapvona as a reaction to the hype of My Year of Rest and Relaxation, a book about a gorgeous, thin, and deeply depressed girl who pops sedatives like candy in hopes to sleep for a year that spawned a TikTok obsession and as Vice puts it, an aesthetic trend. Moshfegh has said that My Year of Rest and Relaxation was, in some ways, a reaction to the Eileen discourse, which mostly centered around the fact that the title character was ugly. “In a way, I made a decision to make this character beautiful partly in response to the reception of Eileen,” Moshfegh told Hazlitt in 2018. “So it’s like I’m going to write an equally complicated female character but make her look like Claudia Schiffer so nobody could make a big deal about the way that she looks as though it’s part of her value.” I ask Moshfegh if Lapvona is in any way a reaction to the My Year hype, if it’s maybe a way to subvert her TikTok admirers.

“No, no,” she says quickly. “No. I think it’s just where my curiosity took me.” Later, she adds: “I mean, I hope My Year of Rest and Relaxation isn’t just for girls who think they’re hot.” I assure her it’s not, but devotees of that book might be utterly shocked when they read Lapvona. “I mean, for all the hot girls out there, this book is for you, too,” Moshfegh says. “It’s for you to read and take away whatever it means to you just like you did with My Year. I wasn’t writing that just for you either, but I love you.”

Lapvona is like a joke that goes so far that you can’t help but laugh, mixed with the pleasant sensation of watching bloody pus ooze from a zit. With Lapvona, Moshfegh might have gotten all the pus out.

“I don’t know for sure, but I think Lapvona is probably where I want to bury that interest, where it will rest in peace now,” she says. “It was something that I really needed to express, like the imagination of all of that and how much it related to…how much the grotesque relates to death, which for me relates to God, and for me that was part of that exploration. I’m not sure, but I think I’m maybe onto the next, at this point.”

Moshfegh wrote Lapvona during the pandemic lockdown, and it’s easy to make connections between that era and the villagers dealing with famine and an inadequate, egomaniac leader who forces Marek to eat sausages until he throws up while everyone in the village is eating dead spiders, dirt, or each other to stay alive. It takes, in her words, a more “anthropological” look at humanity, and is the first of her novels written in the third person.

“It was about so many people that I could actually feel like an author instead of a ventriloquist, to put it in sort of a derogatory way, not to sh*t on my past work,” Moshfegh says. “The perspective felt important, especially because everyone was so isolated and it was as though we were living in third person. It didn't seem like the time for a real introspection narrative.”

The most addictive part of Lapvona is the same thing that draws readers to her other works: how she renders psychological portraits of characters that reflect our own repugnance, and therefore our humanity. She once told Vice, “My writing lets people scrape up against their own depravity, but at the same time it’s very refined . . . it’s like seeing Kate Moss take a sh*t.” It’s an exercise that’s compassionate as it is tactful, one in the tradition of Flannery O’Connor or Katherine Dunn, a rearranging of the world so that everyone who's not a freak is the freak.

Because regardless of how uncomfortable it makes us, cannibalism, rape, incest, and violent religiosity all happen. She’s always been good about writing about the monstrosity within all of us, and making it normal, even making it kind of fun. A book like Lapvona is not for everyone, but it might be for more people than we think. Moshfegh points out culture’s obsession with binge-watching horrific, violent crime docuseries and docudramas, something nobody thinks twice about, but when it’s a book, people suddenly like to moralize.

“When we read, we have to conjure the things for ourselves in our mind and it can feel like an invasion when someone puts a thought in your head that you didn’t want to have, and I get that,” Moshfegh says. “I mean…trigger warning! That’s partly why I wanted that lamb on the cover. Like, you guys, this isn’t about some cool girl.”