Culture

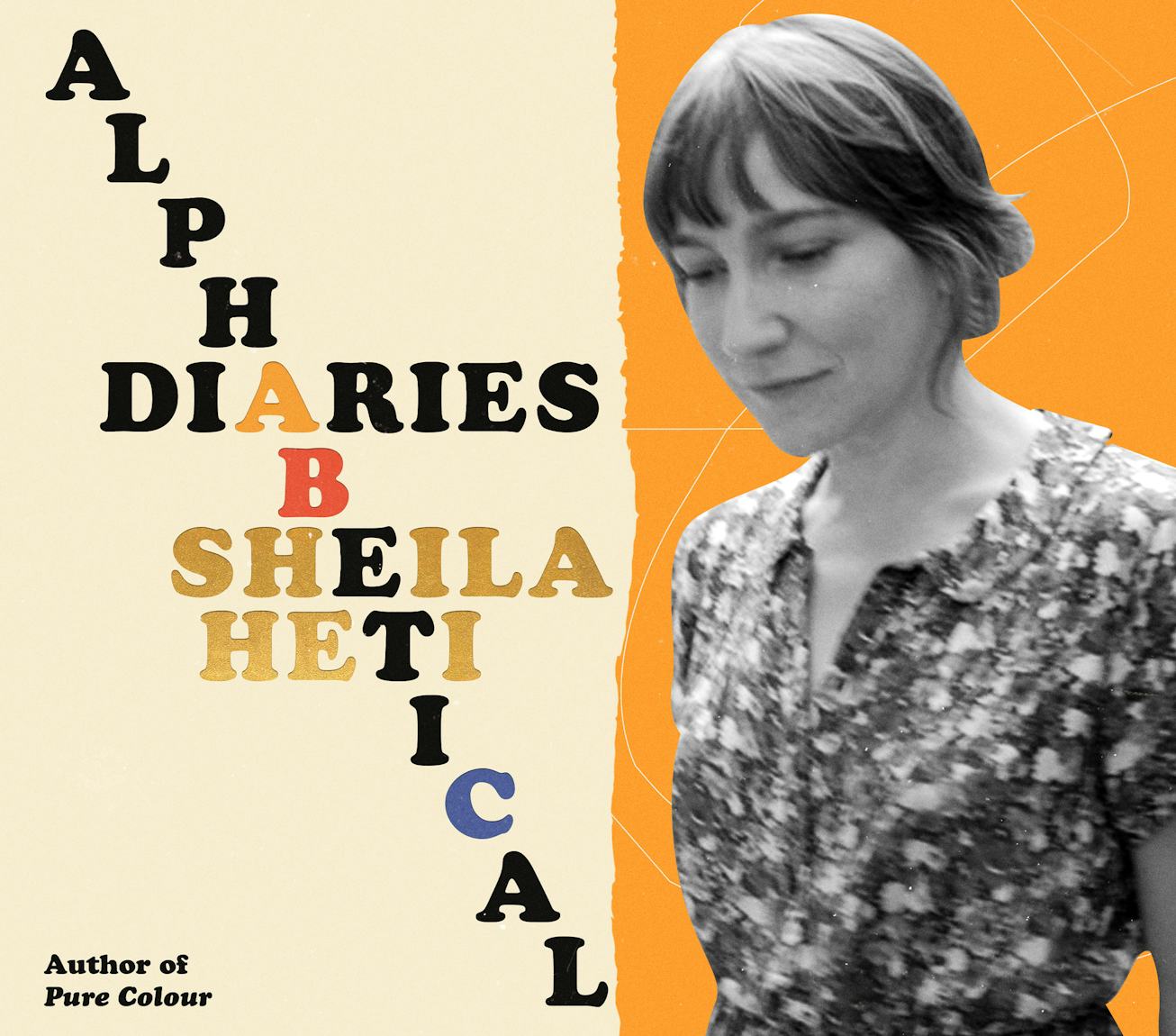

Sheila Heti Is Still Afraid To Have People Read Alphabetical Diaries

Sheila Heti’s letting us in on her deepest thoughts.

Not bothered by convention, brilliantly executed, and intelligent (while somehow remaining relatable) each one of Sheila Heti’s books uses its own tactic to answer a central question. In How Should a Person Be, the narrator uses actual dialogue with friends in order to complete a commissioned play which propels her to search for the answer to the titular question; in Motherhood, the narrator uses three coins to get closer to deciding whether or not she should have a child; and more recently, in Pure Colour, the governing rule (or ruler) is God, sitting back and looking at his first draft of creation in which the central character learns to balance grief with her own inherent desire for beauty and harmony.

In Alphabetical Diaries, Heti makes a stark departure from her previous work, not collaborating with friends, coins, or gods, instead turning her gaze to herself by organizing 10 years of her diary by alphabetizing the sentences. Moments that were separated by years are pushed together, making repetition palpable and poetic. Sentences like “Don’t take anything personally. Don’t take yourself so seriously; don’t think about yourself at all” might’ve been written five years apart, but when placed next to each other they make clear Heti’s interests, like the friction between creative and commercial success, the erotic and the performance of it, and how to exist in an increasingly difficult world.

“It's nice to have found a way to put these thoughts in a book,” Heti tells NYLON. “Most books need to hang those themes on plot, or on multiple characters. And there's no real plot in life. So, how do you get those thoughts in a book without plot, in a way that still seems like it's being lived?”

NYLON spoke with Heti ahead of the book’s release about the impulse behind alphabetizing her diaries, what it was like to publish her deepest thoughts, and more.

What was the origin of this project?

Some things just start. There were probably all these thoughts that happened subconsciously beforehand, but one day I found myself alphabetizing my diary, and it just seemed like the most obvious thing to do. I didn’t know where it would lead to or that I would end up working on it for 14 years. I just thought it was a way to pass the time for a while and it could be interesting. What would I find? How would it read? I think some kind of curiosity probably started it, which is like most of my writing projects.

What was the editing process like?

I thought about which sentences go nicely beside each other. Without editing it would’ve been too boring, there needed to be a combination of things happening, visual descriptions, a movement. You want different textures butting up against each other. I had a million files and sometimes I would go back to previous drafts, where I hadn’t made any cuts and start over again.

Were there any interesting patterns that surprised you?

I was surprised by how little I thought about in those years. I was interested in certain themes, like whether to leave Toronto, how to write, how to be a writer, and my relationships with men. That was kind of it. And then I was like, “What about all the other things? Do I not think about anything else?” But for me, a diary isn’t really for recording what happened, but instead for trying to work through problems. Those were my problems for those 10 years: Where to live? What to do about a man? How to write whatever book I was writing at the time?

People often talk about the narrators of your fiction as being like some version of yourself, whether it’s by sharing the same name or biographical details from your life. This is the first time I feel that we're really getting you. You're giving the reader so much of yourself while also maintaining a barrier of privacy through the alphabetical structure.

This is the first time it's not a character in the book, though, of course, a character does emerge from the editing. But yes, there's this privacy, because the narrative has been broken up. I was still afraid to have people read it, honestly. To have people who didn't know me read it, in particular.

What was that experience like?

I felt like I didn't know what was being revealed of me. I don't know what kind of person is coming across. Whereas with How Should a Person Be there was a character that I was trying to convey. In this case, I'm conveying myself, and I don't know what that is. It's more nerve wracking and scarier. When I gave it to the people close to me to read, I hoped they would still like me. Are they going to think that I'm different from how I present myself to them? The diary isn't really the person that you give other people, but you don't want it to be so different that no one wants to be your friend anymore.

In my experience of reading your books, like with the coins in Motherhood, or the dialogue in How Should a Person Be, there’s a collaborative element to your work. The Alphabetical Diaries feels like an interesting departure from your previous writing.

It's really alone. A diary is far away from other people. It's about as far as you can get from other people, apart from dreaming.

Though at some points, it can be collaborative, between versions of the self. For example, I really enjoyed reading the “I” chapter next to the “Y” chapter, because of the use of the first and second person. It’s like multiple selves coming to the table.

It's such a good question: Who's the addresser and who's the addressee? It’s kind of baffling. Why do we have the idea that there isn’t an addresser and an addressee as though they’re not the same thing? Could they be?

I have no idea. Maybe it’s a way of addressing the self in the future or the past?

Or maybe we recognize that we’re not just looking out on the world, that we are people, for other people.

Are you working on anything new?

I wrote this short story for The New Yorker, called “According to Alice.” It’s taken from an AI project where I've been talking to a chatbot for three or four years. I spend all my time on a computer and my father who passed away was a computer programmer. I wanted to think about his interests. When I thought about it, interestingly, the computer is actually speaking to you from its own pseudo-consciousness, so of course, I had to fold that in.

This might make me seem antiquated, but I am truly scared of AI.

I used to have so many bad feelings, and now I don't have any.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on