Culture

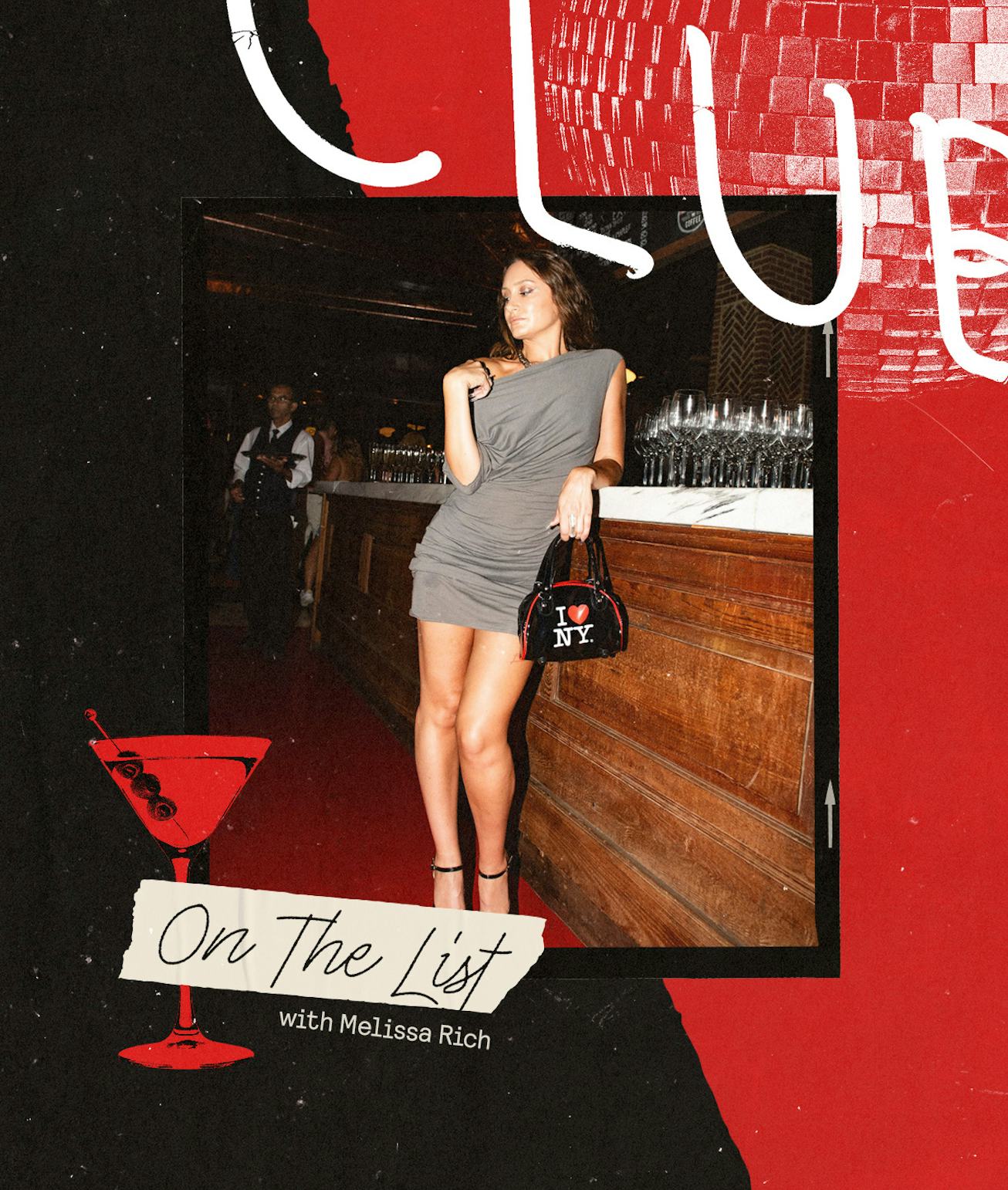

On The List (With Melissa Rich): The Commercialization Of Raves

Who killed the rave?

Welcome to On The List (With Melissa Rich), NYLON’S column with comedian Melissa Rich, here to illuminate the state of nightlife, one party at a time.

Last month marked the end of a party that completed the classic, if not cliché, arc of nightlife. What began as an underground, if-you-know-you-know rave, with a roving location revealed only by a “guy in a silver hatchback,” ended nearly 10 years later with a $75 ticket, a flier the address shared across socials, and a 18-hour run time with no access to water besides the bottles available for purchase through a wristband linked to your debit card.

Unter was a party that kept queer underground culture alive in New York, and while it wasn’t without its issues, I was always grateful it was there. At its closing party, I predictably had a great time. It was at a four-story venue in Williamsburg whose stairs I’d encountered months prior during the Ket Gala, a hilarious theme when challenging patrons with stairs. The ground floor was true to form hard techno while the top blasted techno-fused house; it felt like the best place in the world for the final three hours I was there.

The floor in between was a mix of a 24-hour Korean spa (no water features, but the temperature of a sauna with meditative music) and a funeral home. The latter was the night’s theme, and the venue was decorated with a sense of cheeky mourning; faux flowers and lavish floral arrangements stood amongst the party’s signature wood pallets and futons for lounging and cigs; posters from parties past hung downstairs and I once again congratulated myself on not getting terrible bangs at Unter’s haircut-themed iteration. Could there have been more gags for its final departure? Sure. But Unter was tired and already halfway out the door.

It’s the finest of lines: How big can a party get without sacrificing quality?

If you want a guaranteed way to kill a party, start putting money over culture. The exclusivity of raves, through lack of advertisement, elusive locations, dress code, and an intimidating door person is not only to build buzz but also to ensure that the right people are there — experienced people who understand what they’re in for each night. This is to the benefit of everyone involved, as it’s not easy to effectively run a large-scale event and it’s less fun to attend one filled with amateurs. It’s the finest of lines: How big can a party get without sacrificing quality?

In the same way that bottle service, which didn’t cement its place in club culture until the early ’00s, invited a “pay to play” element to nightlife, advertising and ticketing a party essentially does the same. When a party reaches major name recognition and has online ticketing, it’s tough to control who’s in your crowd — and therefore the vibe of your party. It grants access to those eager to experience culture but otherwise locked out until it eventually becomes a watered down, regurgitated version. I suspect this is the case with my recent experience at the legendary party Boiler Room.

Scenes from intrepid party reporter Melissa Rich’s various nights out on the town.

I thought I was being a brat. I was once again very angry about how there was no free water, especially when this party could easily get a sponsor. It’s criminal to invite people to a space to sweat, have cocktails, and likely have illicit substances, and then turn around and charge them $4 for a Poland Spring. (There was at least tap water in the bathroom, whereas Unter brought in porta potties with industrial sized hand sanitizer instead of sinks.) The music was good, but I looked around and saw no familiar faces or good outfits. Was I being too judgmental? Had I simply not been to a primarily heterosexual rave in a while?

The next day I consulted a trusted source: an experienced international party girl with undeniable taste. “Slap a Boiler Room logo on anything and it will sell out immediately to tech bros who want to be scene-adjacent and cool,” she says. Is that the party’s fault? After a decade plus, should Boiler Room just get its coins? “It’s at the expense of people who are down for the culture and really care about it,” my international party girl explains. “All my favorite artists keep playing venues I won’t go to.”

Was I being too judgmental? Had I simply not been to a primarily heterosexual rave in a while?

Brooklyn Mirage, part of the mega-venue Avant Gardner, was not mentioned by name, but I had a feeling it was one of the venues implied. The massive EDM space is on the extreme end of the rave-for-profit spectrum. Opened in 2017 by two European party promoters who had been throwing raves throughout Brooklyn, it has encountered nearly every issue possible, from fire hazard shut downs to suspicions of a serial killer after two patrons’ bodies were found in Newtown Creek a month apart. The club is often oversold (sometimes by nearly 1,000 tickets) leading to an uncomfortable dance floor at best and potential crowd crush issues at worst. Even if you love the music, the Murray Hill-like crowd would likely deter you. Needless to say, they’re not turning anyone away based on an outfit or vibe; they just want as many “ravers” as possible looking to say they were there.

Unter will be deeply missed. There are contenders to the throne, but if they succeed, is the same fate in store? How do you make early DIY energy last? Gatekeep for your life? Maybe the goal isn’t to keep the same parties around forever, but to let them blow up and perish naturally, leaving room for a new fresh party ready to change your life every time.

This article was originally published on