Entertainment

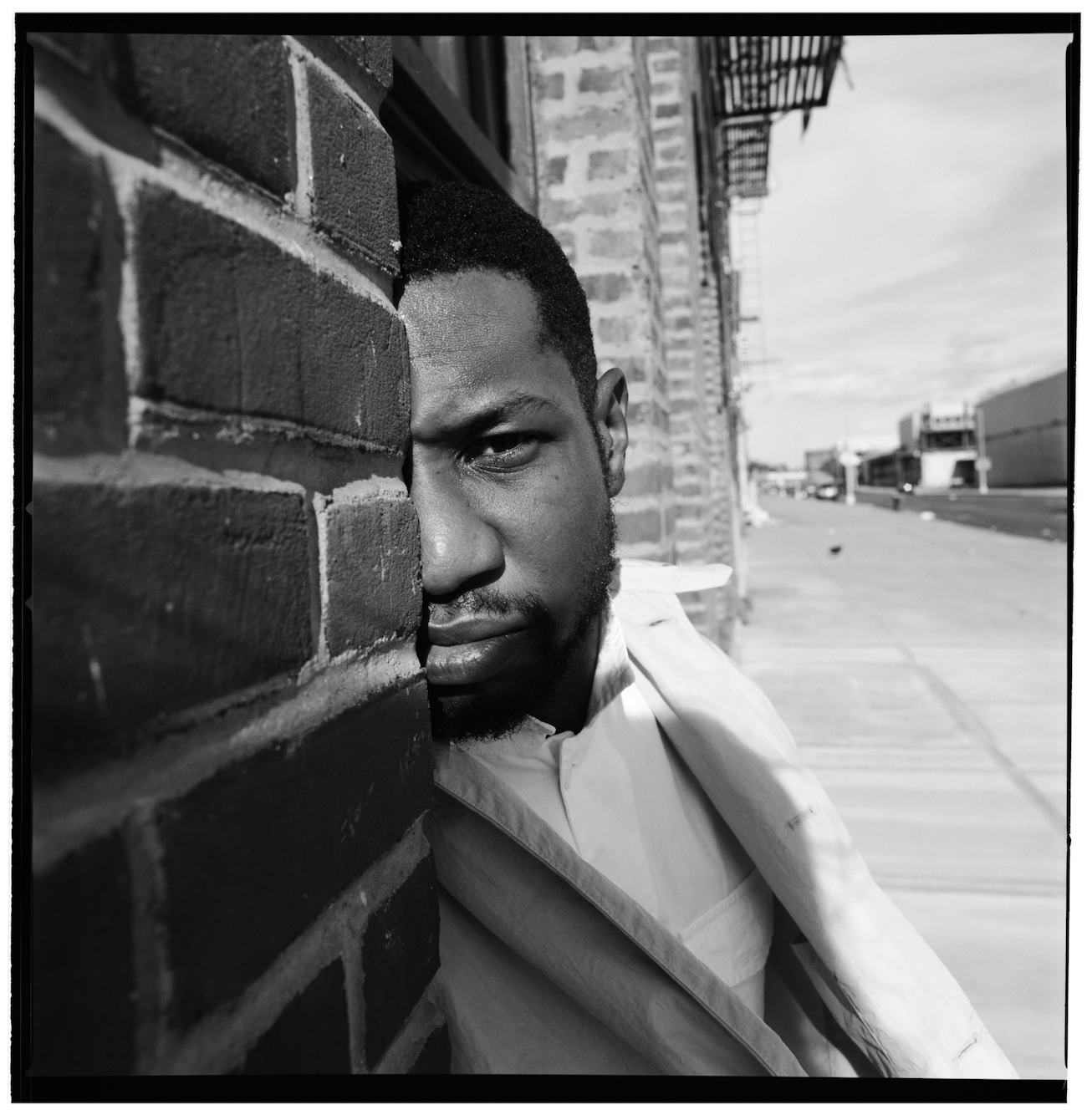

'Da 5 Bloods' Star Jonathan Majors On The Spiritual Reeducation Of America

The Spike Lee-directed Netflix film follows four Black Vietnam War vets on a time-jumping journey.

If Jonathan Majors had smaller feet, he’d probably be rocking a pair of Spike Lee’s secondhand Jordans right now. According to the actor, who had a major breakout in last year’s The Last Black Man In San Francisco, the legendary Oscar-winning director once guided him into a private backroom at his Brooklyn office, showed him “a bunch of Nikes and Jordans, all lined up,” and asked him if there were any he liked. Majors swears the director would have gifted him a pair (or more) right there on the spot, but his size 11.5 feet got in the way.

“Well, I don’t got your size,” the actor remembers Lee telling him. “But I’ll get them for you.”

This all happened the first time Jonathan Majors met Spike Lee, less than a day after Majors got an unexpected call letting him know that Lee had him in mind for his latest joint: a time-jumping war dramedy called Da 5 Bloods. A longtime fan of Lee’s work, Majors was immediately determined to book the role, even if the casting process was “the most unorthodox thing.” In addition to the potential shoe-gifting, Majors also recalls: getting a call from Lee on his personal cell phone, passionately arguing about the Cowboys (Majors is from Dallas), and watching a music video Lee directed for Red Hot Chili Peppers while sitting so close to the director that “me and Spike Lee’s legs are touching.”

It’s the perfect introduction for both the film itself and for Major’s experience working on it. Lee has always been considered an “unorthodox” director, and, with his insistence on telling Black stories with unflinching clarity, has been viewed as a Hollywood outsider for decades. Though Da 5 Bloods feels much grander than his past work (save for maybe 2018’s Oscar-winning BlacKkKlansman), it is still unmistakably Lee, telling the story of four Black Vietnam War veterans who return to Vietnam to hunt for a trunk of gold they buried there decades before. Majors plays David, the son of one of these veterans, who shows up unannounced in Vietnam, insisting that he be included in the treasure hunt. His arrival throws several wrenches into their carefully laid plans, and though he isn’t one of the titular Bloods, his role is a pivotal one.

Now, the 30-year-old actor is gearing up for the premiere of the film, which he maintains is arriving at the perfect time — right as people around the world are taking a stand against the centuries-long mistreatment of Black people in America. During a Zoom call with NYLON, the Independent Spirit nominee opened up about his experience working with one of his idols, the roles allies should play in the revolution, the difference between working with white and Black directors, and the burden of the relationship shared between Black sons and their fathers.

Spoilers for Da 5 Bloods ahead.

You were clearly excited to work with Spike Lee. What was your background with his work?

He’s our griot. He tells our stories without any filter. The film I love the most of his — probably because it’s Spike at his height — is Malcolm X. That’s the dopest biopic in the history of biopics. The chief thing is that we have a Black hero. Malcolm X is our Black hero and he does hero shit. He leads the Nation of Islam. We watch him be the dopest hustler, the dopest gangster there is. We see him get thrown into jail. It was the first time I had seen a Black man with that much screen-time. I saw that movie when I was 14 and I was like, “This is dope.” Then, Do the Right Thing became my impetus to move to New York. I was like, I got to be with these people. These people are so alive. So that was my point of view on the fella, that he was a legend, a griot, and so relevant. I was already a part of Da 5 Bloods when he won his Oscar. So it felt like I was stepping into the lineage of a legend.

Was working with Spike everything you would have imagined?

I found this out. Whatever you think it’s going to be, it’s probably not going to be that. I experienced that when my daughter was coming. I’m thinking, okay, I’m getting ready to become a dad. But then you become a dad and it’s like...there’s no game-plan for this. Same thing with leaving graduate school, moving into the industry. What you think Hollywood is going to be, it’s not that. It’s already changed by the time you get there. So whatever expectations I had for working with Spike Lee, by the time I hit Thailand, it was a whole different ball-game. All the expectations I had were thrown out the window, literally from the first day.

Spike put so much into David, and therefore, poured so much into me — as far as the history of the war, the socio-balance that was going on, the fact that there were wars on many different fronts for the African-American soldiers. They were fighting the Viet Cong, but there was also the Black men vs. white men. They weren’t playing fair. They were putting us on the frontlines to be killed.

There’s an impeccably moving and acute moment in the film where Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King was killed, and there are riots, and they have to hold their dignity and not express their sorrow. At least, that’s what they feel they have to do. They want to fight, they want to kill, they want revenge, they want to get even. But Chadwick Boseman’s character, Stormin’ Norman, says, “Don’t let them take that rage.” And they commence to purge themselves and have a cathartic moment together, with love. I saw that because of the work I did with the people that Spike brought in. War veterans don’t talk much about [the war], but Spike brought them in and they did. I didn’t expect that. I didn’t expect an entire education independent of my work on the film.

In the moment when they get the news about Dr. King’s assassination over Vietnamese radio, the woman doing the broadcast speaks directly to the African-American soldiers, asking them why they’re fighting for a country that doesn’t love them back. She points out how Black people are protesting his murder all across America, and how their presence in Vietnam is preventing them from doing the same. Right now, we are witnessing a very similar cultural moment. How does it feel to be releasing this film now?

It’s a divine weight that I’m happy to carry. It’s ammunition, to stay within the war metaphor. We are armed with a story, we are armed with art. And this stuff is going to permeate and, hopefully, move through the lifeblood and the vein of our country and our world. That was the issue then and that is the issue now — that Black culture is one thing but Black lives are something completely different. So to present a film in this moment — one that is funny and emotional and political; one that is about Public Enemy No. 1, the Black man — it is going to wake some people the fuck up and it is going to support those who are probably fatigued with their protests.

Everybody is engaged in this. Everybody is involved. And to actually be a physical part of it, to be playing a character that holds a deep amount of responsibility for the narrative, oh, I’m ready! I can’t wait for people to see it. David has a specific voice because he wasn’t a war veteran. He’d be one of the protestors. And David believes in education. We’ve got to educate these white folks. We’ve got to educate these people that think they can kill folks. They need a deep education. Well, they need a deep correction. They need an intellectual, emotional, and spiritual ass-whooping — and they need it from all fronts. You want to talk about that war, talk about the war. Talk about all aspects of it, and one of the biggest aspects of that war were brothers who looked like you and me going out there and getting their asses blown to shits.

You play David, the son of Paul, who has the deepest PTSD from the war. Thinking about the strained connection many Black sons share with their fathers, how did you approach that aspect?

Man, I think you’re right on. You’re a brother just like I am. You’ve got a father too, and I reckon that is one of the most tumultuous, emboldening, and enriching relationships in your life. Present or not, your father is your father, and a son’s love is a son’s love. You have to imagine: the father of a Black boy or the son of a Black man — these fellas are dropped into enemy territory from the beginning. The Black father is given an almost insurmountable mission to keep this thing safe. As a Black man, you are the enemy of the patriarchy — at least, you feel that way. You are unsafe. How the fuck are you going to raise another you when you can barely carry yourself? You could be gunned down at any moment. You could be kneed down at any moment.

As far as the film, that’s what made me jump into it. I know what it is to be a Black son, and I’m still dealing and wrestling with that. My father was in the military; he was a veteran. So I understand that dynamic — the discipline you grow up with, the hardness that can be put on you. So looking at the film, it’s even more difficult because this father was not only in a war, but had a very hard time in the war. Then, he comes back home and tries to raise [his son] in another warzone. It’s a war on top of a war and somebody’s not playing fair. But the driving force for David is a son’s love. There’s really nothing that man can do that will stop me from loving him. As mad as I am at my father — my personal father — there’s nothing in the world that can stop me from loving him. It’s the tie that binds us. So I found a great opportunity to bring that to the forefront. Spike is giving us the platform. Nothing has been taken out, none of it has been soft-pitched, nothing has been white-washed. This is the relationship between a Black son and his father.

On the other hand, your character develops a romantic connection with a white woman, who actually ends up helping to save your life later on. While David is appreciative, Paul is clearly very distrusting of her motives. Do you think that was included as a way to speak to allyship? There’s been a huge conversation about the role of the ally recently.

Well, you’re getting to the bottom of the barrel there! That’s one of the underpinning conflicts within any movement, you know? Do you have the right to help? Why are you helping? In some cases, it’s educational. And in some cases, it’s generational. You see that the reason David is [trusting] is because David spent time with [the white woman] Heady. They actually got to talk with each other, they got to share things with each other. She valued him, for whatever reason. She got to know him and he, her. They got to see each other.

Paul was not present in that moment. He has his own way of living. I’d even venture to say he may not have had many intimate interactions like that with someone of the opposite race. So it’s just a matter of ignorance. Paul doesn’t know, he hasn’t experienced that. A lot of times, when there’s distrust between people both doing the right thing, it’s because they haven’t spent enough time together. There’s a deep tribalism in this country that can be very toxic. There’s a distrust. You don’t look like me, so therefore, you can’t really understand what it is that I’m doing. But it’s not a matter of understanding. It’s a matter of contributing. Do no harm.

In addition to working with Spike Lee on Da 5 Bloods, you also recently worked on Jordan Peele’s upcoming HBO show Lovecraft Country. Both Lee and Peele are visionary Black directors — did working with them differ from working with Joe Talbot, a white director, on The Last Black Man In San Francisco?

The brilliant Joe Talbot is not a Black man, but that film was emotional in a different way. With that title, I provided the “Black man” while [Talbot] provided the “San Francisco” and what he saw as the African-American male experience. So that’s a great example of allyship. That’s what it feels like. They were allies helping us and spearheading that narrative. So we are on the same team, we are doing this together.

Now, working with Spike, it felt like we are one. I am no longer interpreting what you’re saying; I’m spouting what you’re saying through my instrument. You’re telling me: Which facet of Blackness are we going to tell in this moment? This one. Okay, I got it. It’s more like they’re inside you versus beside you. We’re all working on the ancestral plane, in a way, because we have a shared history, a shared trauma, a shared joy. In some cases, we have a shared God. So we can just...split it up.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was originally published on