Culture

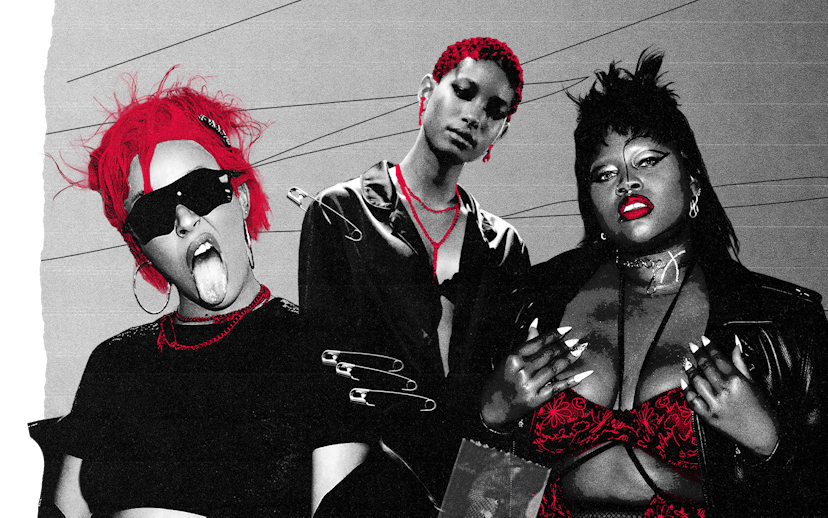

The Infiniteness Of Alt Black Girls

A new dawn of alt Black girl culture is here, thanks to the mainstream success of artists like Doja Cat, Willow Smith, and more.

Re-entering society this year has brought about an assertive identity in young Black people who consider themselves “alternative,” abbreviated as “alt” for the modern digital era, as the subculture gains visual prominence across social media. While alternative subcultures have existed for decades, initially associated with the emo and punk scene outside of mainstream pop culture, these groups saturated with white followers caused alternative Black subculture to naturally form its own entity. Through the connectivity of social media, young Black people part of this scene are being unleashed from the confinements placed upon them, not only by lockdown restrictions but by social expectations of how they should be — entering in the new wave of alt Black culture.

TikTok and Instagram have been instrumental in displaying alt femme Blackness in particular in recent months. Rico Nasty, an artist who’s as punk rock as she is rap, is on the forefront of expanding this alternativeness into the culture. “You know that you’re a Black girl right? Your hair’s supposed to be sewed in not spiked up?” she spits on “Jawbreaker.” Her lyrics have struck a chord, and are recited over and over, by “altblackgirl” TikTok creators. This search term provides videos of Black women rocking experimental hairstyles from neon-dyed braids to shaved mohawks, facial piercings, and makeup looks, lip-syncing anything from trap metal to Willow Smith’s pop-punk “Transparentsoul,” opening up a Pandora’s box of alt Black subculture from a new generation’s perspective.

Black women are typically hidden in the algorithm of these apps when typing in “altgirl,” instigating a segregation that reflects the history of the alternative scene beyond the digital space. “As a Black alt person, the physical space of the alt scene, like the garage band setup, was never my home,” says Melanie McClain, A&R of indie music company Secretly Group. “Listening to alternative music was a solo journey for me.”

Alt music can feel particularly isolating for Black women as listeners and artists in an industry skewed toward men. What is most encouraging now is that alt Black women have found their way to the mainstream with musicians like Doja Cat and Willow Smith alongside Rico Nasty, spearheading bringing versatile femme Blackness to the masses. Doja effectively showcases this in her experimental image and performances, which have ranged from rock to electro this past year. "It is important to have artists" who are different, the rapper said of inspiring alt Black kids. "It’s important to have those kinds of influences in your life when you’re like that and feel completely cast out of…the world.

These artists’ impact has forged the way for underground alt Black women in music, like LustSickPuppy and Junglepussy, to gain more visibility after years performing for crowds within the subculture. These women continue to trample the boundaries set up for them as Black women in music, showcasing an undeterred determination to reach the top. The fashion industry isn’t far behind, embracing alt Black femme more and more. Makeup artist Raisa Flowers’ unconventional trademark look includes bleached and shaved eyebrows, mismatched grills, and bold beauty looks have gained her a large following online — along with an impressive client list. Flowers is becoming one of the increasingly recognizable alt Black femme faces to be booked to model for high-profile brands, including Calvin Klein and Savage X Fenty, encourging a change in the industry in accepting alternative Black beauty.

The questioning of Black women’s appearances rocking facial piercings or tattoos — major staples utilized within alt subculture — serves as a twisted irony as both are rooted in African tribal body decoration. Women of the Mursi tribe in Ethiopia participate in ear stretching from the age of 15, as do Maasai men and women from Kenya. Tattoos and nose piercings link back to that of traditional Indians and the Beja people of Egypt, signifying wealth and prominence. These ethnic connections may have gotten lost in the West, but the aesthetics of the alternative can offer a way back.

Although there’s the argument that Black women shouldn’t have to be labeled as “alt” because of the individual ways they choose to express themselves, the term is seen as empowering for those who are part of the scene. “I embrace being alternative,” says Areana Powell, a contracting spiritual adviser who has been identifying herself this way since age 14. “My mum put me onto Metallica, Asking Alexandria, and more heavy metal music when I was in high school. Tyler the Creator came out around this time, too, ushering in the ‘Black emo wave.’ Alt music opened my mind into depths of me that I used to condemn.”

Being alternative as a Black person can cause rejection from inside the community, which Powell, now 23, says she experienced. “I felt outcast from my race. My family was called demonic, but my parents helped me feel comfortable being different.” Feeling totally displaced can be a lonely space, but social media has helped bridge connections for Black alt people in this position. “Instagram, Reddit, and now Twitter are the places I find other alternative black women,” Powell adds. “It’s like we were all hiding in Tumblr spaces, but now we’re all out here having fun and I’m so happy seeing it.”

Growing up in the era of Myspace, McClain first found her community there. “Everyone used it as a social app. In the message boards, I was extremely active in the same way you have Twitter friends now.” Through music, she’s been able to identify with being alternative. “That’s the space of alt culture I feel comfortable in. Alternative is not just one way. It’s me defining it for myself.”

Physical spaces are equally important for the Black alternative experience. McClain has found living in Brooklyn, New York, to be a great environment for the scene to flourish. “Brooklyn helps you embrace the greater perspective of alternative Blackness. New York normalizes it. It makes me feel understood.”

Brooklyn is also home to Afropunk, one of the most established and acclaimed Black alternative festivals. Co-founded by James Spooner and Matthew Morgan in 2003 for the Black punk subdivision in NYC, Afropunk debuted the same year the documentary of the same name took a deep dive into the alt scene across the United States. Other festivals have since been created, providing spaces for alt people of color, no doubt inspired by the success of Afropunk, including Decolonise This based in London and Bla/Alt Festival based in Charlotte, North Carolina.

From headliners like FKA Twigs to niche artists like IAMDDB and Moonchild Sanelly, Afropunk’s diverse acts over the years celebrate the message that Black people “can be so many different things,” a message expressed in the documentary by early punk performer Ryan Bland, now lead singer of NYC hardcore group Ache. Black alt pioneers like Lenny Kravitz, Grace Jones, and Erykah Badu have also performed, part of a generation of influential figures in the subculture before the digital age allowed it to further thrive, showcasing that Blackness truly is infinite.

Social media now has become vital to those who feel outcast in their surroundings or yearn to relate and discover more to the scene, as McClain did creating a group on Clubhouse in the midst of the lockdown. “Every single Friday, I host a New Music Friday room. It’s called Blurred Lines and it’s about Black artists who blur the lines of genre and have an alternative perspective,” she says. “There’s no other space for these people. I’d love to see in the future Black people centred in alternativeness.” Powell echoes these sentiments: “I hope younger generations continue to embrace being Black and being authentically themselves.”

This article was originally published on