Entertainment

Reckoning With Pop Music’s Villain History

From Madonna to Lil Nas X and Charli XCX, musicians have long exploited that centuries old trope equating pop music with moral corruption.

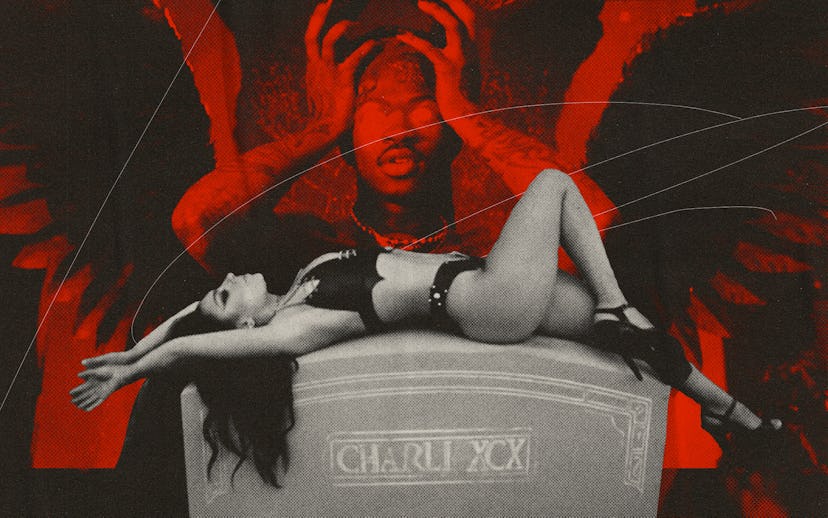

Charli XCX is in her villain era. Months after the release of her pandemic project how i’m feeling now, which was a vulnerable real-time take on creating during quarantine, evidence on social media demonstrated that she was shifting to the darkside. Bloodied images, horror movie stills, demon fairies, and a cartoon devil flooded her social media feeds. “I like evil popstars,” she tweeted in 2021. A week later she wrote, “Tip for new artists: Sell your soul for money and fame.” She shared a picture of an email thread with her label Atlantic Records and another sender, takemysoulforever666@gmail.com, bcc’d, implying that her deal was done and her soul was ready for the taking. She made a full Elvira pivot with “Good Ones,” the lead single of her forthcoming album, Crash. In the music video, she cavorts at a funeral, causes holy bibles to combust, and dances on her own grave. At the visual’s end, she passes out, implying her death at the birth of a new album cycle.

Despite the tongue-in-cheek tone underlying Charli’s performative 180, many reacted to her posts as if she was a serious cult leader or embodying some malevolent force or both. Commenters asked her to repent and find god. Even spelling out her album’s intention wasn’t enough for people to back down: “a thought: imagine if this entire album campaign was just a commentary on navigating the major label system and the sadistic nature of pop music as a whole ?” she tweeted in January. Later, an onslaught of backlash for her announced involvement in the NFT festival Afterparty (she later dropped out) and displeasure from fans with the album’s singles resulted in her taking a step back from social media. It was a striking lapse between the sexy villainous persona she promoted on social media and the menacing judgments people felt emboldened to share online.

Oddly enough, in an era where we’re constantly warned not to take the internet at face value, Charli told the internet she was turning evil, and they believed her. But as she enters what’s been dubbed her “main pop girl moment,” she’s playing into an important cultural trope that equates pop music with moral corruption. We’ve progressed from Paganini and Robert Johnson, musicians whose myths rely on their relationship with the Devil, to Madonna and Lil Nas X, who exploit that centuries old stereotypical relationship with popular music. Some artists expose that playing the villain is either more fun or honest.

A pop villain chapter, whether intentional or not, is a rite of passage. The change in narrative is usually both a strategic move to break out of a creative or career stalemate and a reaction to how an artist feels they are perceived. Some artists conjure evil alter egos like Nicki Minaj’s persona, Roman. Some artists try to break free from innocent beginnings like certain Disney Channel artists or—less chaotically—Rihanna. "I'm my own [person] now. Not doing what anyone wants me to do. I'm not the innocent Rihanna anymore. I'm taking a lot more risks and chances,” Rihanna said of her album title for 2007’s Good Girl Gone Bad. Her reinvention was built on bad girl behavior, which symbolized liberation and capitalized on a sexy image.

A pop villain chapter, whether intentional or not, is a rite of passage.

Paula Harper, an assistant professor of musicology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, points out that Charli’s campaign is in conversation with pop stereotypes as well as capitalizing off shock in a meme and viral obsessed culture. “[There’s a] deliberate invocation of the sacred as a way of producing outrage that is marketable or is profitable. It feels like a connection to that older model like Madonna where the visibility and the branding potentials for celebrities were in a new mediated way with Music Television and more prevalence of visual media. There’s a definite parallel here with social media as being this new space for branding and expression,” she explains. The result is a frustrating dissonance that exists between art and our capitalistically driven world. “There’s this kind of ouroboros, a snake eating itself, where at this point we’re also in a space of critiquing the machine that can be something that goes viral.”

Dorian Electra, an experimental pop artist who’s also a frequent Charli XCX collaborator, however, adds that playing the villain isn’t always that deep. Sometimes it’s like “playing goth for a day.” Despite a creator’s intention, Electra notes that the tension of our politically polarized climate impacts the perception of any transgressional art. “Especially now under capitalism, where every kind of identity and political identity can be commodified, [intention] is sort of meaningless,” they say. “In a way, you can be saying, ‘fuck the system,’ by participating in that exact same system and doing nothing towards it, other than making people feel good that they are, like, supporting an artist they are ethically aligned with, but they're making no material difference in the world.”

As a public figure, villainization is a cruel part of celebrity: the onslaught of criticism that comes as a reaction when an artist doesn’t play into the expectations or norms of the time. In the best cases, the artist will lean into the act of what they’re being villainized for. When Madonna was threatened with arrest by police at a 1990 Toronto show if she insinuated masturbation on stage, she slunk further into her sexual performance. The police cited she would be arrested for “immoral live performance.” That label implies condemnation of human pleasure and specifically female pleasure, which until artists like Madonna were introducing it into their art, was confined to the jail of taboo.

Noting the constant cultural oscillation between authenticity and grandeur, Electra argues “there’s something inherently sexy about being the villain.” Playing with dichotomies—good and bad or pure and evil—is a way that artists can explore the complications of human nature. “When you go online, I think so many people experience negativity about them and their career,” they say. “I think embracing that being like ‘You know what, who cares? Ya everyone fucking hates me.’ There’s something powerful in that.”

So much pop cultural art that leads to shock, which leads to outrage, is when artists confront audiences with the uncomfortable. Never has a society loved to hear that word, let alone cozy up to it, or spend the night with it. Taylor Swift commented on the expectation for artists to constantly reinvent themselves towards the end of her Miss Americana documentary. “Live out a narrative that we find to be interesting enough to entertain us, but not so crazy it makes us uncomfortable,” she said.

When M.I.A. made her rise as a British artist of Sri Lankan descent, she reminded the world of how limits of discomfort are different for non-white artists. “What experience are we allowed to share from these places that makes you comfortable and easy for you to digest,” she expressed in the film Matangi when criticized for bringing awareness to the violence and genocide in Sri Lanka throughout her career. “They feel that I have way more responsibility to be this global world poster child like, ‘Hi, I’m the starving child from the mud hut that made it. I’m always going to stay that way just for you so you get the message.’”

In 2021, when Lil Nas X was promoting his debut album, Montero, he exploited the homophobic hate from conservative and religious trolls by selling satanic shoes and playing the devil in his videos. Harper says, “That feels more like Lil Nas X addressing the assumptions already there around him because of the identity that he inhabits in the world, right? This is what a young gay Black man has to work with and so he's gonna inhabit it, rather than somebody like Taylor Swift or Miley Cyrus who can put it on, but then also have the capacity to be like, ‘No, wait, just kidding, I'm innocent.’” Harper considers Charli’s current Satanic Panic-inspired campaign to be commentary for “how silly it is that this technique and strategy is a way to sell music.”

Taylor Swift’s sixth album, Reputation — which music critic Maura Johnston dubbed Swift’s “heel turn,” — leaned into the villainizing tabloid fodder from her feud with Kanye West and Kim Kardashian. When Swift was called a snake online, she made it her mascot. Under a waterfall of backlash and people questioning her authenticity, she became the queen of what her detractors had dubbed her. But, if anything, the most uncomfortable part of her Reputation villain plotline was not her complicating a famous controversy, but the reminder that so many white woman pop stars rely on Black American stereotypes within their most extreme album cycles. Swift employed hip-hop and trap music on Reputation to help make her point. At the end of the day, or the album cycle, it was part of a performance she could remove. As quickly as she slid into her role as the queen of snakes, she shed her skin and leaned into innocence; her follow-up album was called Lover.

So, while playing the villain can be fun, the implications of pop villainy can be different depending on an artist’s identity. We expect pop artists to constantly surprise us, but not change the aspects about them we love. Additionally, not all artists are granted the same creative freedom, which shouldn’t come as a surprise in an incredibly unequal world.

Alice Glass, a Canadian singer-songwriter and former frontwoman of the popular electronic group Crystal Castles, discusses the confusing villainous narrative around her on the internet. She tells me over the phone how her malevolent reputation was fabricated through false headlines and misogynistic reporting. “I’d get known for being a brawler and fighting in mosh pits, it would be like, ‘Oh, she fought me for no reason.’ But it was always because I was crowd surfing and somebody tried to put a hand up my skirt or somebody was feeling me up,” she says. “I would follow the arm and I would see the person and if their face was like, smug, then I punched them.”

Years after exposing the abuse she endured from her previous music partner in Crystal Castles, her solo punk-oriented pop music is an expression of her rage. “I kind of want to be this dark reminder. That makes me a villain in the music industry,” she says with a laugh. “But I want to be somebody that you think of before you sign a contract, or before you work with a producer. Or before you listen to any guy who says something to you, and then acts another way.”

When it comes to pop villainy, most of the time, the artists themselves are not the bad guys. Instead, they’ve used scintillating earworms and seductive marketing to exploit the absurd concept that equates morality with taste. “A lot of people are embracing the quote unquote villain because it’s a time when our cultural values are unclear. So it’s like, maybe the bad guy does have a point,” Electra points out. The massive backlash against Charli XCX speaks to the ongoing moral panic that climbs out of the grave like an intolerant zombie every time pop culture threatens cobwebbed puritan norms. Pop music’s history with villainy is a blatant reminder that our moral compass has always been wildly askew, and that its rise is a signal toward a reckoning.